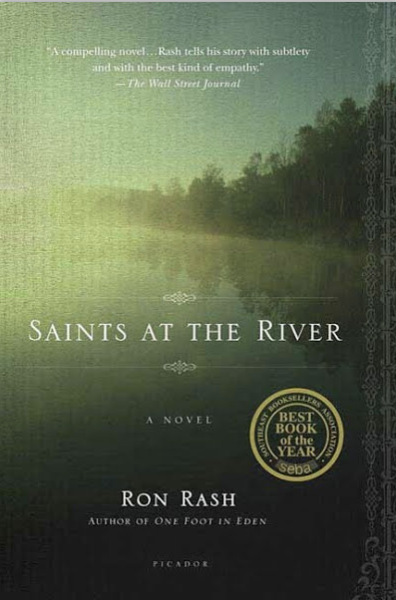

I’m trying to figure out a way to encourage my students to read and take notes in a way that’s productive. After watching some videos by a high school teacher named Tim McGee, I’m thinking about something like the reading notebook he encourages his students to keep.

McGee’s system asks you to divide each page into two halves: the left hand side for before class and the right hand side for during and after class.

On the left side, you track: 1) what happened in what you read (i.e. a summary), 2a) what it means and 2b) how the author says it, and 3a) what other literary works the text under discussion reminds you of and 3b) what personal events the text reminds you of.

I’m leading a reading group discussion of Jane Eyre this summer, so I’ll be keeping the journal as I read it to use as a model. I listened to this episode of In Our Time today to simulate the classroom lecture I was taking notes on. I was really encouraged by how the process worked, and I’m excited about honing it for use in the fall. Who knows? I might even start using it for my Bible reading.