Where do you fight writer’s block? On the front lines of your research through effective note-taking. But not all notes are created equal, and not all reading is done the same way.

Start by recognizing that reading itself is a multi-stage process:

- In Inspectional Reading, you skim the material to decide if it’s worth a deeper dive. This is your first pass, helping you prioritize your research efforts.

- In Analytical Reading, you engage critically with the text, dissecting arguments and evaluating evidence. This is where deep understanding begins to form.

- In Synoptical Reading, you compare multiple texts on the same topic, synthesizing information across sources. This advanced stage allows you to create connections and generate new insights.

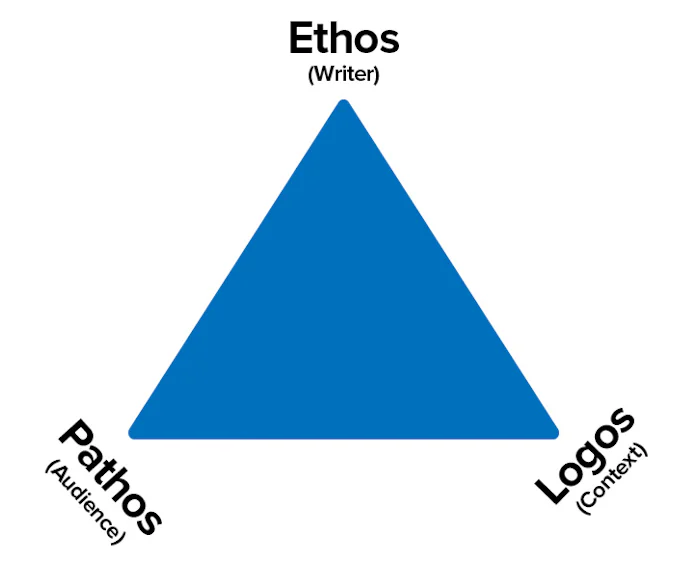

Just as reading consists of different stages, effective note-taking involves three distinct types of notes. Per Sönke Ahrens’s helpful book How to Take Smart Notes, here are three kinds of notes to keep distinct:

- Fleeting Notes are the quick, spontaneous thoughts that pop into your head as you read. For example: “Project-based learning increases engagement – check impact on test scores?”

- Literature Notes capture the main ideas or arguments of a text in your own words, along with the bibliographic data. For instance: “Johnson & Lee (2023) found that gamification increased student participation by 37% in online courses.”

- Permanent Notes are the crown jewels of your note-taking system: standalone ideas written in full sentences, as if you’re explaining the concept to someone else. These notes get the drafting stage started as soon as you’ve read something. For example: “The effectiveness of gamification in education raises important questions about long-term learning outcomes and the balance between extrinsic and intrinsic motivation.”

Each stage is a process of distillation, where you add clarity and depth to your understanding.

To truly harness the power of note-taking, consider these strategies:

- Always read with “a pen in hand” to capture those fleeting thoughts.

- Write concise, selective notes in your own words.

- Develop a workflow that transforms your fleeting and literature notes into well-formulated permanent notes.

- Use labels and tags to create connections between ideas.

- Regularly review your notes to uncover emerging research projects.

Adopting this system can revolutionize your research and writing process. It combats procrastination, increases flexibility, and eliminates the feeling of wasted effort. By externalizing your thoughts, you reduce cognitive load and free up mental space for new insights. Moreover, this approach enhances your ability to generate ideas and produce drafts for multiple projects.

As Sönke Ahrens wisely notes, “Writing is, without dispute, the best facilitator for thinking, reading, learning, understanding and generating ideas we have.” By integrating smart note-taking into your research routine, you’re not just collecting information. You’re taking notes that can transform into powerful tools for combating writer’s block and generate new ideas.